THE DANCER AND THE DANCE: PHILOSOPHY AND ACCOMPLISHMENT IN THE WORK OF DANIEL RAMIREZ

ARTS MAGAZINE / FEBRUARY 1982

O chestnut tree, great rooted blossomer,

Are you the leaf, the blossom or the bole?

O body swayed to music, O brightening glance,

How can we know the dancer from the dance?

- W.B. Yeats, “Among School Children”

________________________________________________________________________

THE DANCER

AND THE DANCE:

PHILOSOPHY AND

ACCOMPLISHMENT IN THE

WORK OF DANIEL RAMIREZ

Robert Glauber

Daniel Ramirez sees his art – all art – as a reflection of the grand order that underlies everything. He is much interested in making viewers think as in making them feel; in making them react as much as act. So he strives endlessly “to illustrate thinking” and seeks, by his art, to organize our vision.

Intellectual history has periodically been enriched by theorist-creators who have regarded their art as primarily an extension of their thought. They have understood painting-or novel writing or music or poetry-as an articulation of their abstract ideas into visual-or aural or written-form. They have seen all their creative work as an effort to set down in formal terms concepts that are essentially intellectual. In extreme cases, they considered their lives, their ideas, and their works as an indissoluble entity. In a way they could never explain, they all sought to make their ideas and the realization of them one and the same; to make perception and reaction simultaneous.

Richard Wagner was one such theorist-creator; Wassily Kandinsky was another. So were Gustave Flaubert, Franz Kafka, Arnold Achoenberg, Barnett Newman, and most of the early Surrealists and Abstract Expressionists. All saw complex philosophical purpose in their art. All sought an ancient goal; a unity of art and life; a bold and original, all encompassing “conclusion” about what Art is. I wonder how many of them ever read Flaubert’s bitter observation: “Ineptitude consists in wanting to reach conclusions…What mind worthy of the name, beginning with Homer, ever reached a conclusion?”

Fortunately for such theorists-creators, when they are really first rate, the search is all. The unending search is the driving force. Most abandoned their systems, precepts, and philosophy when hot creativity took over. Their drive to do new work in response to new stimuli, to express themselves as individuals, overrode their philosophic inclinations and systemic limitations. Possessed, they did what their creative forces dictated, not what their intellects tried to impose. Order gave way to inspiration.

All of these people (and others you can name) tried to transubstantiate thought into art. Is that possible? They tried to make their theories usurp their creative work. Is that possible? It is interesting to note that it is their work, almost without exception, we now prize. Their theories we ignore, regard as historically “interesting,” or, at best, tolerate.

Daniel Ramirez is an artist-theoretician who, by his own ready admission, falls comfortably into this group. It is not surprising that in 1978 when Ramirez was awarded a fellowship to complete his PH.D at the University of Chicago, it was not in the Department of Art but rather with the Committee on the History of Culture in the Department of the Humanities.

When you know his work, when you hear him speak, you see at once the logic of this. Ramirez, is above all, a student of systems; philosophical, musical, and religious. At the University he was particularly interested in the work of Ludwig Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein His M.F.A. thesis, Expression as Tautology: “The Selfish Act” (a Case for Metaphysical Man), was, as he wrote, an indirect approach to the concerns of

To sum up very briefly the three main concerns in Ramirez’s thought and art: 1) He is fascinated by Wittgenstein’s theses of interpersonal communication; 2) he recognizes similarity between Wittgenstein’s systematic approach to logic and the twelve tone row-scale Twelve-Tone Music developed by Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg, and Anton Webern: 3) he seeks to combine strictly logical thought (personified in Wittgenstein) with creative intuition (as in Schoenberg, et al.) and attempts to apply them toward a clearer understanding of Thomist Thomist Theology theology. All of this must be rendered, then, into visual terms as drawings, paintings, and prints. Ramirez has adapted Descartes to his own need: I think; therefore I paint. And he is more comfortable with this perception than any other artist I know.

If all this sounds excruciatingly incondite, unnecessarily complex and even a bit precious, Ramirez would readily admit that it probably is. He is a good teacher (at the University of Illinois, Chicago Circle Campus) but is aware that his ideas, like his paintings, are not for everybody. He wrote: “My own work exists only for personal reasons. It is necessary to what I am, and I hoe I’m able to discriminate when I am not doing something worth looking at.”

Despite his philosophical underpinnings, Ramirez’s work, like all good art, is primarily an effort to present what Wittgenstein termed “communicable ideas.” Like Wittgenstein, Ramirez is willing to “pass over in silence” what he cannot communicate. So his is an art of balanced tensions and releases. It stems from an interplay with the seeable and the intuitive, the knowable and the instinctive. His work is not based on natural forms ( as with the Abstract Expressionists) but on systems and patterns of pure thought. It is a precisely engineered bridge between the philosophic (and musical) systems that intrigue him and the physical phenomena he must use to express them.

Ramirez is one of those students of philosophy who believes that phenomena determine theory-not the other way round. So he uses his extraordinary craftsmanship to give visual form to his ideas. He uses a repertoire of images that is self-restricted and formal, sometimes to the point of iciness.

At first glance, Ramirez might appear to be just another geometric abstractionist. One can read his work as a limited number of geometric forms (triangles, rectangles, and the trapezoids that result from their combination) differentiated by subtle gradients of pale colors, grays, whites, and blacks. In such a reading, Ramirez’s content would consist of the relationship of the forms, their arrangement and discipline. As such, he would merely be another follower of Albers’ dry lead.

But geometry is only the point of departure. Ramirez is not interested in shapes as such. He is as much concerned with the way we see as with what we see. He is interested in those strange quirks in our vision that makes straight lines bend and circles seem elliptical. (As in sophistry, ideas can be given the appearance of truth without being true.) Ramirez has dug down to the roots of how we perceive what we see. Thus he is allied to the ancient Greek architects who, by inventing entasis, curved the steps of the Parthenon to make them appear flat and bowed the columns to give them a straight look.

You can never be sure when you look at a Ramirez canvas if things are what they seem to be. Flat-appearing canvases may actually be curved, and gentle curves may be an illusion of color, shading, and form. This constantly shifting ground is one of the most fascinating aspects of his work. He makes us see what he wants us to see, not necessarily what is there. He deliberately confuses us to mar the usually sharp distinction between reality and illusion, between poet and reader, between what Yeats terms “…the blossom and the bole…the dancer and the dance.”

Ramirez is very interested in music. He has played the double bass professionally and is particularly fond of the works of Bach, Schoenberg, Webern, and Messiaen. He is accustomed to an aural world of great and subtle complexity. It is not surprising, therefore, that he orchestrates his series of drawings, paintings, and most recently, intaglio prints in terms of formal counterpoint. He answers one line with another as in a canon, uses the concept of theme and variations, elaborates ideas through an increasingly complex polyphony.

This is more than a hyperbolic or poetic reading of his work. In many cases it is conscious and calculated parallelism on his part. It is not mere poetic license that has led to such titles as Verklarte Nacht (two paintings) and Bild fur S,W,B @ 12 ( 12 graphite drawings with the S,W,B, standing for Schoenberg, Webern, and Berg). These are all Ramirez’s constructions in visual terms of musical values-values, not content.

A recent suite of 20 etchings is another example of the weaving of music into his art. Entitled Twenty Contemplations on the Infant Jesus: An Homage to Olivier Messiaen Messiaen , The prints and their prepatory drawings are a tribute to a musician Ramirez greatly admires, as mystic as much as composer. They are, in Ramirez’s mind, equivalent but personal expressions of Messiaen’s special sensibility to the life of Christ.

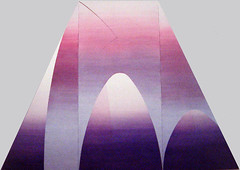

Like the music, the prints are 20 variations on simple forms. There are three main leitmotifs in the music woven through many of the sections. Ramirez is equally bound by three forms. Like the music, the prints are tightly composed. The tonal range is small, the dynamics rigorously controlled. An ff in the music is as striking as a large area of matte black in a print.

The reverential theme (as both composer and printmaker understand it) is always there. Yet there is never even a suggestion, much less a depiction, of the Infant, the Cross, God the Father, or any of the other obviously theistic elements that make up the titles of the prints and form the core of most religious art.

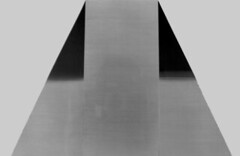

The prints are all done in warm, infinitely varied grays, often cut into incredibly sharp black lines. Bold forms are set down in the deepest, darkest, lushes of blacks – a special tribute to the skills of Chicago-based printer Dennis McWilliams. The use of white space on the large sheets (like the use of silences in the music) is just as significant as the color. The two embossed triangles of The Kiss of the Infant Jesus are separated by slowly gradated bars of ink that run from jet to a whisper of gray. Ramirez feels that as we decrease our resistance to Christ, a need for traditional symbols fades. The literal bars of the print fade and both Christ and the print become more accessible.

Like Messiaen’s music, Ramirez is creating a mood from a visual image that reflects both feeling for the music and sound theology. He is concerned not with the conventional trappings of religion, not with any ritual observances, but with an inner devotion, a private world of the spirit that can open doors of mystical love to those sharp enough to perceive the keys his works proffer.

The print’s, like most of Ramirez’s work, started with rough postcard-size sketches. Then came the more precise full-scale study drawings. The plate-making involved the exhausting process of trial, dissatisfaction, revision, and applied ingenuity common to all good printmaking. Etching, drypoint, electrically vibrated drypoint, aquatint, engraving, mezzotint done with needles, rockers, brushes, and razors were all used to create the effects Ramirez wanted: extremely fine brittle lines; blind printing, both raised and lowered; almost imperceptible gradients of shading. Making the prints was, as is always for sensitive artists, a lesson in patience and possibilities.

Twenty Contemplations is a suite of prints which, in their initial showing at the Art Institute of Chicago (January-March,1981), struck viewers with their utter simplicity and openness – a simplicity and openness that can be achieved only through the dogged elimination of absolutely everything not essential to the final vision. That process of refinement was clearly revealed by the presence in the exhibition of the 20 full-scale study drawings and many of the trial proofs, some of them in successive states. Ramirez pared his images until he had the sharp angularity, the sudden and arresting switches in directions, the darkness, the light, the silences of Messiaen’s music and, above all, the deep faith of both men.

Ramirez came to his interest in technique by a singular route. He did not go to art school until quite late; at 31 he enrolled in a class of late teenagers. He felt that, at his age, he had to listen, to absorb, to learn all his teachers were offering him on a now-or-never basis. He knew he had to prove himself quickly, with none of the indecisions and indiscretions allowed the youthful. So he took in everything his more-than-willing teachers offered him. He often speaks now of the debt he owes his instructors for both the information and encouragement they lavished on him.

He was a high school dropout who grew up in a tough, non-Latino neighborhood in Chicago. After dropping out, he did a stint in the Marines. Then he drove a truck for twelve hard, frustrating years. There had always been art in his half-Mexican, half-Croatian home. His father had a natural talent for illustration and his mother was very interested in music. But neither meant very much to him when he was young. He was adept at drawing in school, but it was a skill he accepted passively.

The twelve years in the tuck cab began to take their toll. He feared that the grind was wearing away his individuality. So he took to reading (at first Vance Packard and Studs Terkel); then he began to ask questions and philosophy offered some expansive answers. In 1971 he left trucking and enrolled at the Chicago campus of the University of Illinois. He wanted to study illustration and commercial art, following the lead of is father. Fortunately, the University offered no such course so he entered the general foundation program and threw himself into the work almost desperately. It is a tribute to the quality of instruction at the school and to the perception of his teachers that within one year he was invited into a student show. Less than two years later, still in school, he had his first professional one-man show.

The early canvases look like Ramirezes. He understood his aesthetic preferences from the start and could express them clearly, on canvas and in words. For about two years he made boldly colored works, sharply differentiated forms that dealt with the relationships of volumes and space. Through layered blues and greens slash pale green and orange lines to set the edges vibrating and hold the eye. Reality (such as bottles, walking figures, running water) was reduced to formal, logical shapes no longer holding any realistic associations. The paintings were essentially still lifes abstracted as far as Ramirez’s skills were then able to carry them. But for the theorist in him, they were works that fulfilled their potential too completely.

These early paintings were on a route that many others had traveled. Ramirez was a good abstract painter with an eye for unusual juxtapositions, more subtle than most other artists interested in optical effects, but the canvases seemed to say all they had ton say at once. They held nothing back for the participative imagination of the viewer and so were dead ends. They were just too self-contained for Ramirez’s comfort or satisfaction. He now considers them part of a valuable learning process.

So Ramirez started in earnest to apply to the making of art some of the philosophical, musical, and theological principles he had been exploring. He now felt better equipped to probe Wittgenstein’s thesis that every logical picture, by its nature, can contain contradictions of space that reconfirm its own tautological position as both knowledge of a subject and the subject itself. (A clear example of this is the Necker-Cube.) In the music of Schoenberg, Ramirez found the same equivalencies. Schoenberg’s tonal relationships deal with two interacting rows of musical language that move back and forth, relating only to themselves, dealing only with pure music.

Ramirez now understood that Wittgenstein, Schoenberg, and Thomist theology all deal with closed systems concerned only with themselves. They contain no certain knowledge applicable to the world beyond themselves, yet they all aspire to touch on it. This was a period of intense study, of driving labor to apply these concepts to the surface of a canvas and to find ways in which to use space and color to open both his own and the viewers mind.

Within a year he had refined his ideas and the painterly expression of them to the point where a distinctive style emerged – a harmony of forms, their proportions, colors, and order. A surface relationship to minimalism was now apparent, but inner complexities, seeming extensions of the visual planes beyond the canvas, the mysterious luminosity of the colors (including black), the sense of hushed wonder the large works inspired, all combined to make Ramirez’s work wholly his own. It roused an almost cult-like following in his many Chicago supporters, from collectors to critics, with widely differing aesthetic commitments. By 1977, every canvas was sold before it was dry. So it continues.

In a somewhat frustrating way, I have always found an emotional relationship between Ramirez’s work of 1976-77 and many of the huge, glowing landscapes of Caspar David Friedrich. They look nothing alike, of course. But the moods Friedrich consistently summons of awe at the splendors of space, of amazement at the mysteries of light, are far more significant than his mere depiction of dramatic vistas.

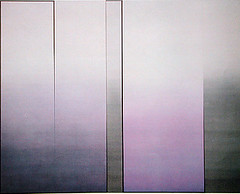

The same is true of Ramirez. TL-P 6.421 (Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago) consists outwardly of two large panels joined together and slashed by sharp verticals of purple-black separating red-violet-gray sections that fade away as they rise from the ground like dispersing mists, all floating before a spiritually pale pink-purple background. That’s what it looks like. But the TL-P is Wittgenstein’s “Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus” and the 6.421 is the section reading: “It is clear that ethics cannot be put into words. Ethics is transcendental. Ethics and aesthetics are one and the same.” Ramirez is here courting a visual-emotional experience for the viewer that conveys Wittgenstein’s sense of identicality, a painting that is ethically binding as it is aesthetically pleasing. Friedrich’s paintings were as aesthetically pleasing as they were intellectually challenging.

None of this is to imply that Friedrich had a direct influence on Ramirez. The artists to whom he is most openly indebted are Rembrandt, Redon, Seurat, Rouault, and in other ways, Mondrian and Newman. Rembrandt, Rouault, and Newman all used black as pivotal focuses of composition. Rembrandt particularly pulled subject matter into the light from intensely rich brown - black backgrounds. Rouault sculpted his figures in textured blacks. Newman was almost obsessional about the placement of his “zips,” the black bands on the canvas. Redon used black to point up ambiguities.

All of these elements have found their way into Ramirez’s work – adapted, transmogrified, subservient. The immense drawing done early in 1978, TL-P 5.6-5.641 / and she had black hair / ALSO (96 by 132 inches), brings many of them together in a particularly fruitful fashion. Rembrandt’s drama, Roualts sculptural sense, Newman’s immense care in the placement of the elements, Redon’s feeling for multiple meanings – all are present, plus something else. The drawing is primarily an exploration and a celebration of light. Through the use of intensely deep blacks – graphite used as both color and texture – Ramirez summons light out of darkness. The drawing seems to glow from behind.

The work was executed during a period of marital crisis for Ramirez. It was, in the artists words, …a reflection of conflict…an expression of love…an attempt to communicate the private, ineffable characteristics of love in universal terms.” Thus the drawing became an expression of both his emotional state and his feeling for his first wife.

Again, Wittgenstein’s “Tractatus” figures in the title. The section this time is a long one covering several interlocking ideas. First the statement, “The world is my world,” then continuing, “The limits of language mean the limits of my world,” were clearly used by Ramirez as justification for the ominously dramatic nature of the drawing, the bold severity of the composition, the two sides pulling apart from the expanding area of the middle. The words and she had black hair is a reference to a fact about Ramirez’s wife and ties her to the drawing’s key color, a luminous, layered black. Also is the artist’s assertion that since he can express himself in a medium beyond the limits of language, he can move beyond the limits of his world.

Yet for all its controlled structure, Ramirez has kept fluidity in the piece. The grays and blacks shimmer back and forth as changing light does in a darkening sky. What you see at one glance may not appear when you look again. That is part of the ineffable aspect of art and again derives from Wittgenstein: “Whatever we can describe at all could be other than it is.” (The drawing won the prestigious Logan Award at the Art Institute of Chicago’s 1978 “Chicago and Vicinity” exhibition and is now part of the Institute’s collection.)

Ramirez is a consummate technician. His canvases are painted with a matte evenness (often using an adaptation of house paint) that seems almost machine - made. He can grade a color from dark to light with a smoothness that suggests a blush rising to the surface of the skin. He uses his preferred brand of German graphite with virtuosity. How many artists can create an impasto with graphite? I know of no others. But through patience, fanatic care, an absolutely steady hand, and the power to stay at the drawing board for ten hours at a stretch, the graphite is built up, stroke by stroke, until it becomes three-dimensional. The surfaces shimmer, are deeply ridged, with their jagged edges capturing and reflecting light in exquisite variety. Once such a build-up process is started, it cannot be halted. It is a non-stop procedure. A stroke up produces one sort of light, a stroke down another.

There is always a special reverence for technique in Ramirez’s ideas. He insists that thought be straight and clearly expressed – on paper as words or on canvas and paper as images. He has trained himself to produce images that are, in themselves, extremely beautiful, beyond any significance they may have to his art. On more than one occasion he has explained that as an artist uses the total of all the techniques made available to him by history, he cannot do so passively, merely as a sponge. An artist must add to that total whatever he can for others to see and use. Thus, in some small way, the artist repays the past for what he uses from it.

Unlike many of the systemic theorists, Ramirez is much more interested in the beauty of his works. He is, of course, concerned with the system from which they are derived, their form and order. But he is also keenly aware of the power of beauty in a canvas to capture the attention and make a general point. This is, unfortunately, not a common concern with many painters today. They want to express themselves, to seek new functions for art in the world, to redefine in highly personal terms what art is. They are not particularly concerned with how there art looks to others: they regard the quest for beauty as an outmoded employment. As a result, many artists today are propagandists for highly personal points of view as much as, if not more than, artists. Chris Burden and Vito Acconci come most quickly to mind. They are willing to sacrifice the “look” of a work if it conveys their message.

Ramirez does not advocate his vision of beauty for anyone else. He understands that deliberate ambiguity about such a quality is necessary and desirable in art today. It was not so in the past. But in a work like “Weisses Bild: Gaudium et Spes, Ramirez feels he has achieved a unity of concept and execution, of form and idea, of appearance and implication or, at least, as close to a unity as he has so far come. For him and the viewer, the work is beautiful – the end-product of accomplishment, not an independent quality. But perfect beauty lies ahead, still to be found and realized.

It may sound from what I have written that Ramirez’s work has a cold intellectual look, that is unemotional. Nothing could be further from the truth about the art or the man. Usually laid back and calmly macho- looking, Ramirez has a volatile personality that swings from calm to storm as the emotional winds blow. Despite their ordered surfaces, restrained colors and cool looks, the works are often very arresting. In exhibitions they stop people in their tracks. Has Anyone Seen The Snow Leopard? (Ramirez’s version of Peter Mattiessen’s quest for the elusive beast-ideal) is done in radiant silver-black graphite that rivets the attention as a cat does with the semi-reflective depths of its eyes. The drawing seems to stare back, a disconcerting experience. In its own way, on its own terms, it is as winning as logic and as wooing as music.

Ramirez has had six one-man shows in Chicago galleries plus museum shows at the University of Illinois in Champaign-Urbana in 1977, the University of Chicago in 1979, and the Art Institute of Chicago in 1981. A major debut exhibition takes place in Los Angeles in March.

His art burgeons as does his thought. His new works are physically more complex than any that have preceded them. The canvases are now often sculptural. Weisses Bild: Gaudium et Spes, a work based on one of the prints in the Messiaen suite, utilizes a stretcher that flares out at one point, runs from thin to thick at one end, and draws the canvas back at one point to make a shadow-compositional line where none exists. There have been experiments in which the central panel has been painted and the remaining sections suggested for the viewer with string and tacks.

There are now vast areas of dazzling white – tightly textured and catching the light from every angle. There has been much talk about a return to bright colors. Red, which has not been used since 1974, floats in and out of conversation , a color with high emotional and theological overtones. Whenever you see him, the artist bursts upon you with new plans for paintings and new ideas.

For an August exhibition, Ramirez turned to photography. He became briefly literal and used music manuscript paper as a bridge between his images and his desire to visualize certain aspects of musical theory. The prints he made were stark and smooth with an architectural look. It seemed logical. Music paper and a draftsman’s graph paper have much in common.

Will Ramirez follow this lead? He has made a few other prints in the series, but it is hard to say, even for him. This fructifying decision is as it must be with a person who is artistically curious and intellectually alive. The solution to one problem automatically suggests another problem.

Ramirez’s reading also expands. He has recently turned to Shusaku Endo’s novel Silence and based several canvases on his interpretation of Endo’s vision of faith and suffering. He has also become interested in Etiennne Gilson’s Painting and Reality, a detailed exploration of the differences between what is visible and what is real. He continues to theorize and speculate. While preparing this article, simple questions often brought forth far-ranging responses that were more attempts by the artist to clarify and expand his own thinking than answers to my inquiries. Like any good artist-philosopher, he is wary of final solutions.

In essence, Ramirez is a classic rather than a romantic artist, one who appeals to the inner eye rather than to the gut. He sees his art – all art – as a reflection of the rand order that underlies everything. He is as much interested in making viewers think as in making them feel: in making them react as much as act. So he strives endlessly “to illustrate thinking” and seeks, by his art, to organize our vision, as the 12 tone composers ordered their music and so our hearing, and as Wittgenstein ordered his logic and so our thought processes. Perhaps, like Shusaku Arakawa, he strives toward “a new definition of perfection.”

Ramirez would use his considerable skills as theorist-creator to learn all there is to know about whatever subject he is investigating: himself and his relationships (infinite); the Mystery of the Infant Jesus (ineffable); the relationship of ethics and art (they are one and the same); the ultimate form (silence), whatever.

But no artist, philosopher, or scientist can ever succeed in gaining, much less expressing, such knowledge. For, as George Schaller phrased it in another connotation: “There is no ultimate knowing. Beyond the facts, beyond science, is a domain of cloud, the universe of the mind, ever expanding as the universe itself.” Deep down, as philosophy student and artist, Ramirez knows this. But he continues the search – the unending search. There is no choice. As he said, his work is necessary to what he is.

Return to Ramirez@Luz Web Site